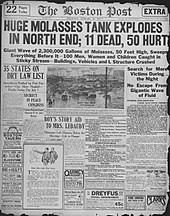

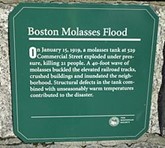

The Great Molasses Flood, also known as the Boston Molasses Disaster, occurred on January 15, 1919, in the North end neighborhood of ‘Boston. According to This Day In History https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/molasses-floods-boston-streets it happened this way:

“The United States Industrial Alcohol building was located on Commercial Street near North End Park in Boston. It was close to lunch time on January 15 and

Boston was experiencing some unseasonably warm weather as workers were loading freight-train cars within the large building. Next to the workers was a 58-foot-high tank filled with 2.5 million gallons of crude molasses.

Boston was experiencing some unseasonably warm weather as workers were loading freight-train cars within the large building. Next to the workers was a 58-foot-high tank filled with 2.5 million gallons of crude molasses.

Suddenly, the bolts holding the bottom of the tank exploded, shooting out like bullets, and the hot molasses rushed out. An eight-foot-high wave of molasses swept away the freight cars and caved in the building’s doors and windows. The few workers in the building’s cellar had no chance as the liquid poured down and overwhelmed them.

The huge quantity of molasses then flowed into the street outside. It literally knocked over the local firehouse and then pushed over the support beams for the elevated train line. The hot and sticky substance then drowned and burned five workers at the Public Works Department. In all, 21 people and dozens of horses were killed in the flood. It took weeks to clean the molasses from the streets of Boston.”

According to Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Molasses_Flood The temperatures in Boston had risen above 40 degrees Fahrenheit climbing rapidly from the frigid temperatures of the preceding days. On the previous day, a ship had delivered a fresh load of molasses, which had been warmed to reduce its viscosity for transfer. The tank collapsed at approximately 12:30 p.m. Witnesses reported that they felt the ground shake and heard a roar as it collapsed.

The collapse translated this energy into a wave of molasses 25 ft at its peak, moving at 35 mp. The wave was of sufficient force to drive steel panels of the burst tank against the girders of the adjacent Boston Elevated Railway’s structure. Buildings were swept off their foundations and crushed. Several blocks were flooded to a depth of 2 to 3 ft .

Molasses, waist deep, covered the street and swirled and bubbled about the wreckage. Here and there struggled a form—whether it was animal or human being was impossible to tell. Only an upheaval, a thrashing about in the sticky mass, showed where any life was. Horses died like so many flies on sticky fly-paper. The more they struggled, the deeper in the mess they were ensnared. Human beings—men and women—suffered likewise.

A large storage tank filled with 2.3 million U.S. gallons] of molassses, weighing approximately 13,000 tons, burst, and the resultant wave of molasses rushed through the streets at an estimated 35 miles per hour , killing 21 people and injuring 150. The event entered local folklore and residents claimed for decades afterwards that the area still smelled of molasses on hot summer days.

The disaster occurred at the Purity Distilling Company facility at 529 Commercial Street near Keany Square. A considerable amount of molasses had been stored there by the company, which used the harborside Commercial Street tank to offload molasses from ships and store it for later transfer by pipeline to the Purity ethanol plant. The molasses tank stood 50 feet tall , and contained as much as 2.3 million US gallons.

Many of these people worked through the night, and the injured were so numerous that doctors and surgeons set up a makeshift hospital in a nearby building. Rescuers found it difficult to make their way through the syrup to help the victims, and four days elapsed before they stopped searching.

Cleanup crews used salt water from a fireboat to wash away the molasses and sand to absorb it, and the harbor was brown with molasses until summer. The cleanup in the immediate area took weeks with several hundred people contributing to the effort, and it took longer to clean the rest of Greater Boston and its suburbs. Rescue workers, cleanup crews, and sight-seers had tracked molasses through the streets and spread it to subway platforms, to the seats inside trains and streetcars, to pay telephone handsets, into homes, and to countless other places. It was reported that “Everything that a Bostonian touched was sticky.

Cleanup crews used salt water from a fireboat to wash away the molasses and sand to absorb it, and the harbor was brown with molasses until summer. The cleanup in the immediate area took weeks with several hundred people contributing to the effort, and it took longer to clean the rest of Greater Boston and its suburbs. Rescue workers, cleanup crews, and sight-seers had tracked molasses through the streets and spread it to subway platforms, to the seats inside trains and streetcars, to pay telephone handsets, into homes, and to countless other places. It was reported that “Everything that a Bostonian touched was sticky.

In the wake of the accident, 119 residents brought a class action lawsuit. It was one of the first class-action suits in Massachusetts and is considered a milestone in paving the way for modern corporate regulation. The company claimed that the tank had been blown up by anarchists because some of the alcohol produced was to be used in making munitions, but a court-appointed auditor found USIA responsible after three years of hearings, and the company ultimately paid. Relatives of those killed reportedly received around $7,000 per victim (equivalent to $109,000 in 2021)

This disaster also produced an epic court battle, as lawsuits were filed against the United States Industrial Alcohol Company. After a six-year-investigation that involved 3,000 witnesses and 45,000 pages of testimony, a special auditor finally determined that the company was at fault because the tank used had not been strong enough to hold the molasses. Nearly $1 million was paid in settlement of the claims..

Many laws and regulations governing construction were changed as a direct result of the disaster, including requirements for construction oversight. The case also completely changed the relationship between business and government. All the things we now take for granted in the business — that architects need to show their work, that engineers need to sign and seal their plans, that building inspectors need to come out and look at projects — all of that comes about as a result of the great Boston molasses flood case.

Boston was experiencing some unseasonably warm weather as workers were loading freight-train cars within the large building. Next to the workers was a 58-foot-high tank filled with 2.5 million gallons of crude molasses.

Boston was experiencing some unseasonably warm weather as workers were loading freight-train cars within the large building. Next to the workers was a 58-foot-high tank filled with 2.5 million gallons of crude molasses.

Cleanup crews used salt water from a fireboat to wash away the molasses and sand to absorb it, and the harbor was brown with molasses until summer. The cleanup in the immediate area took weeks with several hundred people contributing to the effort, and it took longer to clean the rest of Greater Boston and its suburbs. Rescue workers, cleanup crews, and sight-seers had tracked molasses through the streets and spread it to subway platforms, to the seats inside trains and streetcars, to pay telephone handsets, into homes, and to countless other places. It was reported that “Everything that a Bostonian touched was sticky.

Cleanup crews used salt water from a fireboat to wash away the molasses and sand to absorb it, and the harbor was brown with molasses until summer. The cleanup in the immediate area took weeks with several hundred people contributing to the effort, and it took longer to clean the rest of Greater Boston and its suburbs. Rescue workers, cleanup crews, and sight-seers had tracked molasses through the streets and spread it to subway platforms, to the seats inside trains and streetcars, to pay telephone handsets, into homes, and to countless other places. It was reported that “Everything that a Bostonian touched was sticky.